The Future of Global Governance

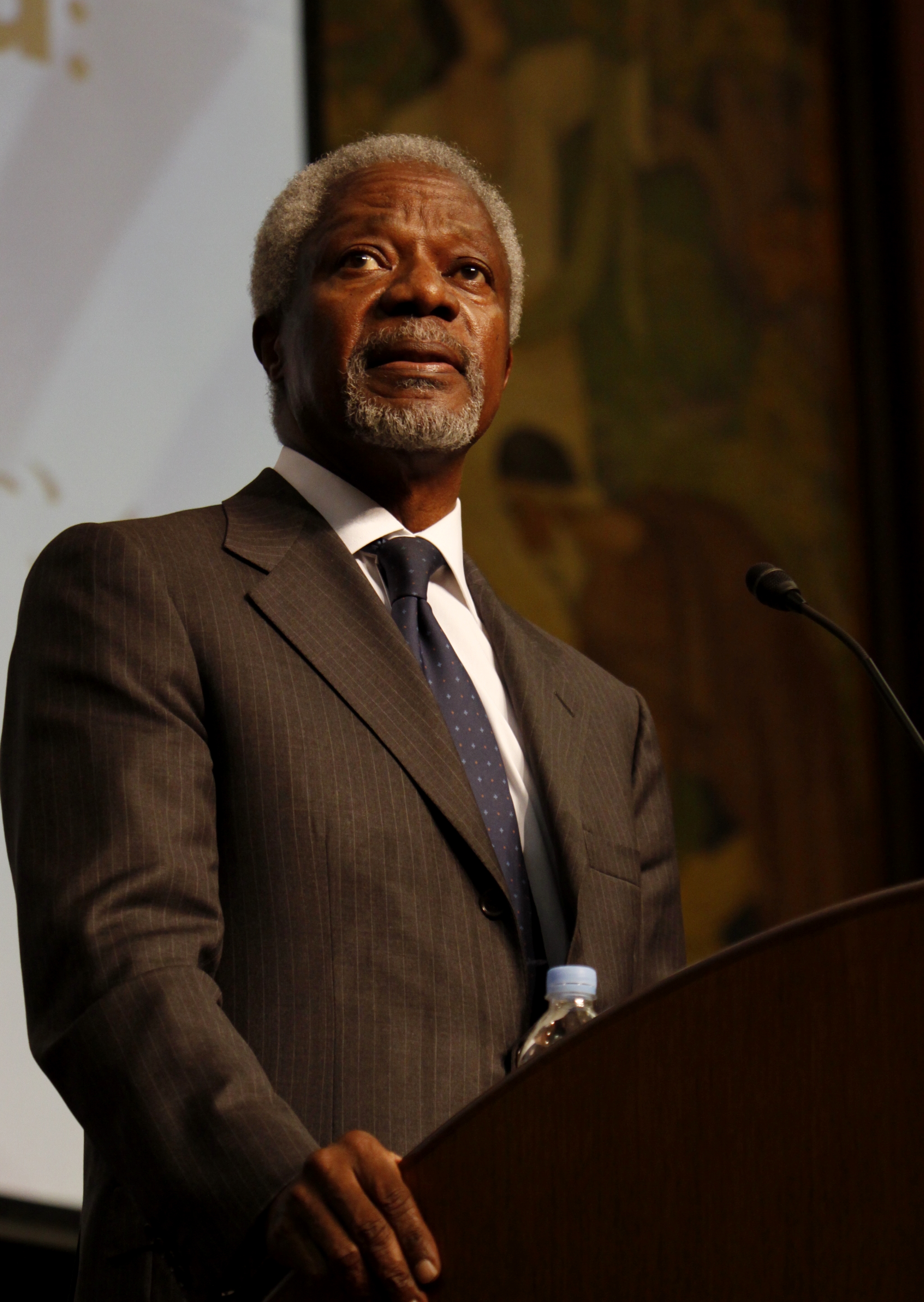

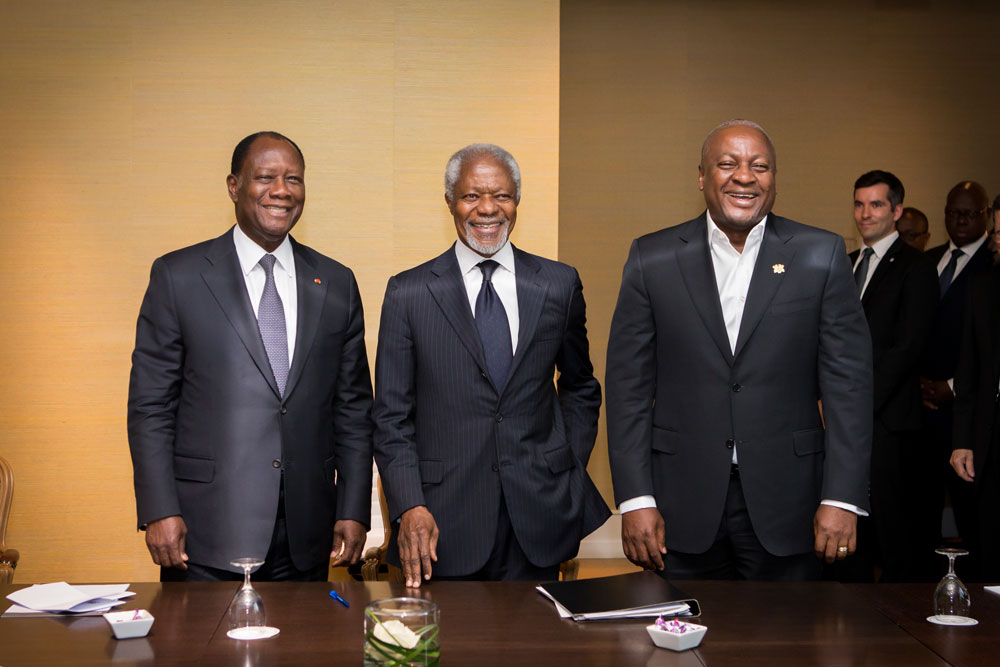

At the German “Zeit Foundation” organised side event at the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference, Kofi Annan spoke about the “the future of global governance”.

I am pleased to be here today at the invitation of my good friend Ambassador Ischinger and, of course, the Zeit Foundation. The Zeit Foundation has demonstrated a welcome interest in global governance over the years, having founded the Bucerious Summer School on Global Governance and the Asian Forum for Global Governance.

Let me use this opportunity to encourage the creation of an African Forum on Global Governance to serve the continent, which is at the heart of many of the global issues of our age. When I am asked about global governance, I am sometimes tempted to say it would be a good idea.

There is a common perception that the world is falling apart, and that our global governance structures are powerless. Even the EU cannot seem to find a sensible and effective regional response to the refugee crisis.

The drivers pulling countries apart within regions are not dissimilar to those that are fragmenting the world order: the lack of political will to think beyond nations’ own immediate self-interest. As a result, the multilateral order as we know it is increasingly divided and contested.

It is also increasingly obvious that the machinery of global governance set up after the Second World War is past its sell-by date. The Security Council’s composition needs to be updated to better reflect the modern realities. The real question is how?

The Bretton Woods institutions’ governance mechanisms too have failed to keep up with the times. Even recently-created institutions like the International Criminal Court are being challenged.

Three of the five permanent members of the Security Council – the United States, Russia and China – have not ratified the Rome Statute, and some African countries are contesting its legitimacy and impartiality. When the whole world is changing, institutions cannot remain static without putting their legitimacy at risk.

But change is difficult, especially for established powers who fear they will lose their privileges. Yet the risk is that without negotiated change, re-emerging and rising powers will be tempted to create parallel structures of regional governance that may compete with the ones that already exist.

There is nothing wrong with regional bodies and solutions. Indeed, they were even foreseen in the UN Charter, under chapter 8, but they must complement rather than compete with the existing global architecture. Despite obvious failings, I do not believe that the existing governance mechanisms need to be replaced wholesale by a new system.

Whatever the shortcomings of the international system as we know it, never before in human history have proportionally so few people died from armed conflict. This is because the international system, composed of rules and institutions, does allow most states to settle most of their disputes peacefully, most of the time.

Nevertheless, to paraphrase Prince Lampedusa, “everything must change for everything to remain the same”. Such reform should encompass the manner in which the heads of the UN, the Bank and the IMF are selected.

The Security Council has to be reformed to give a greater role to emerging countries who can play a bigger part in international peace and security. The Bretton Woods institution must grant voting rights proportionate with countries’ economic weight. This would strengthen their ability to deal with future financial and economic crises more effectively.

Newly powerful states also must recognize their own interest in reforming rather than disrupting the international order. Institutional change is possible, incremental though it may be. The creation of the Human Rights Council, which has grown in stature since its creation during my term in office, is an example.

But the reform of the structures of global and regional governance will require imaginative and determined leadership, and the willingness of privileged states to make concessions in order to preserve the overall system. In this complex and interdependent world, leadership that just looks at the next elections, or the next shareholder meeting, is no leadership at all.

Statesmanship is about leading for the next generation, rather than the next elections. I hope, therefore, that the Zeit Foundation will carry on with its governance fora for the young and promising leaders of tomorrow who must take forward this agenda of renewal. As I often say: You are never too young to lead.