In Search of a New Order

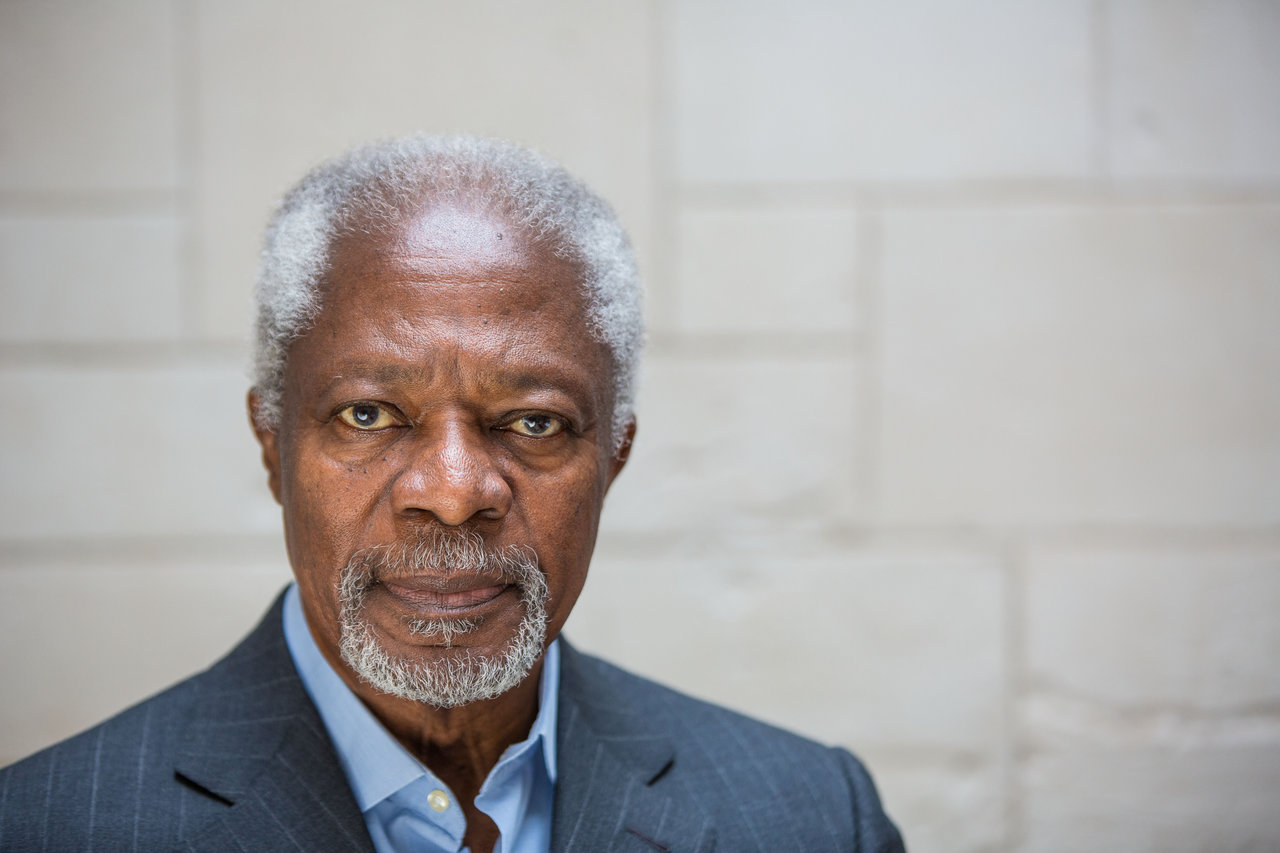

During the celebrations of German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier’s birthday in Berlin, Kofi Annan’s keynote speech outlined the challenges of a new world order.

INTRODUCTION

Your Excellences, ladies and gentlemen It is a pleasure to be here to address you on what Henry Kissinger has called “the ultimate challenge to statesmanship in our time”: reconstructing the international system[1].

It is not exactly what I had imagined when Frank initially mentioned that he was inviting me to his 60th. But I should have known it would be more than just a casual meal among friends.

I could not refuse the invitation of such a distinguished friend, however, a man who is actively trying to adapt Germany’s foreign policy, and Europe’s, to the challenges of our age.

The issue before us today has been at the forefront of my own mind for years, and my reflections, which I will share with you today, underpin the work of my Foundation.

NEW WORLD DISORDER

The words of the elder President Bush spoken before Congress in 1990 still resonate in my mind:

“A new world order can emerge: A new era—freer from the threat of terror, stronger in the pursuit of justice and more secure in the quest for peace. An era in which the nations of the world, east and west, north and south, can prosper and live in harmony…”[2]

To recall those words today is to measure how short we have fallen from our collective aspirations in the aftermath of the Cold War. Instead of the new world order foretold, there is a growing sense of world disorder.

Our open, rules-based world and the universality of democracy, human rights and personal liberties seem at risk[3]. There is growing concern that the very openness of our borders are being exploited by criminals.

These trends are distressing to all of us, but particularly so to a country like Germany, no doubt, which has made such an unerring commitment to open society, the peaceful resolution of disputes and the rule of law, both domestically and internationally, since 1945.

Yet I would argue that we should not overstate the gravity of our current situation. Despite the tragedy unfolding in the Middle East, in wider historical and geographical perspective, our world is actually more peaceful than it ever has been, though we are indeed experiencing a new surge of violence[4].

Even terrorism, which is very much on our minds at the moment, is nothing new and has never triumphed. Liberal states have defeated terrorism in the past and can do so again.

A bigger threat to liberalism is fear itself, which can lead to over-reaction and miscalculation under popular pressure for security and vengeance. That being said, there is no arguing that, compared with the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, geopolitics is back with a vengeance[5].

But geopolitics never really went away. It was just kept under control by the overarching power of a global hegemon – the United States, during its “unipolar moment”. As we know, however, the failures in Afghanistan and Iraq ultimately revealed the limits of even the most powerful states, and eroded their legitimacy.

The Great Recession of 2008 also questioned the economic soundness of the system. As a result, the Obama administration has pursued a more cautious policy, which his opponents have interpreted as weakness.

Though one can question certain individual decisions, I think the US administration’s general approach has been wise rather than weak. It recognises the shifting balance of power in the world. For even if the US’s economy has proved characteristically resilient and the next administration is more assertive, neither will change the underlying trends.

LOST IN TRANSITION?

The world may not be lost in transition, ladies and gentlemen, but it is struggling to find its way. This transition is not due to the fall of the West, which remains by far the most successful group of nations in the world, but rather to the rise of the Rest.

Overall, this is good news: the past few decades have seen hundreds of millions of people all around the world lifted out of extreme poverty. When our current world order was established in 1945, the United States represented about 40% of the world economy. Today, it only represents about 16%[6]. China’s represents 17%[7]!

China’s rise is the most spectacular, but other countries too, like India, Indonesia or Brazil, have seen phenomenal growth, even if they are experiencing a slowdown today. This spectacular growth has been fuelled, at least in part, by demographic growth, 90% of which has taken place in the non-Western world[8].

In short, the West, which has dominated the world for over two centuries, will gradually become less central to its affairs, even if it remains a key player.

BACK TO THE FUTURE?

When some people speak of a new world order, they sometimes mean a post-Western world order. Yet we know that new world orders usually only emerge from major wars between great powers.

It took the Napoleonic Wars to create the Concert of Europe, the First World War to create the League of Nations and the Second World War to create the United Nations.

None of us wants to contemplate the kind of geopolitical upheaval that would be required to usher in another world order. Besides, it is not clear what would replace it, or indeed if it would be an improvement.

More importantly, however, I think that the world order we have is in need of adjustment, not abolition.

ORDER AND ASPIRATION

Any world order rests on two key pillars: a body of norms that are regarded as legitimate, and the power to enforce those norms. None of the rising powers contest the universalist norm at the heart of the UN Charter: national sovereignty.

On the contrary, many states use national sovereignty to contest the more aspirational dimension of international law, enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Yet, even as some governments increasingly chafe at these norms, and question their universality, we see a global civil society emerging out of their populations that is clamouring for these norms to be enforced[9]. In any case, I see no alternative body of norms that could take its place.

Indeed, the loss of relative power of the West could even make those norms more acceptable, because less intertwined with the perception that they are merely instruments of Western dominance.

A NEW BALANCE OF POWER

Likewise, I do not think that the shifts in the balance of power need spell the demise of the international system as we know it, as long as it adapts. After all, the system was designed as a compromise between democratic principles, represented by the General Assembly, and pragmatic reality, embodied by the Security Council.

China already being in the Security Council, it has no need or desire to call the system into question. Indeed, China’s contribution to the UN is increasing as its global ambitions grow.

Other rising, or re-emerging, powers too need to get a place at the table to reinforce the legitimacy of the system. Let us not forget that the USA, Russia, France and the UK together represent only 7% of world population today, yet they still represent 80% of the permanent membership of the Security Council. This cannot last indefinitely.

The established powers must accept reforms that bring emerging powers to the table, thus encouraging cooperation instead of destructive competition. They must also lead by example. All too often, the permanent members themselves have undermined the norms that uphold the system on which they rest, and set precedents, which others exploit.

New and re-emerging powers, in return for more say in the Council, can and must become responsible stakeholders in the system. A world in which power is more diffuse might indeed lead to confrontation, but it could also lead to a more balanced world order, in which the collective powers keep the ambitions of their peers in check.

Going forward, addressing threats to international peace and security will depend less on the intervention of a single global hegemon, or bargains between just two major powers. Instead, we will see more negotiations between changing constellations of global, regional and local players, as the Syrian crisis has already demonstrated.

Diplomacy will become more complex, but also gain in importance. I believe that the United Nations will assume greater relevance, as there will be more need than ever for multilateral solutions, as we saw at the COP21 in Paris.

CONCLUSION

I have not given you some grand new vision for world order in the twenty-first century. But as Helmut Schmidt once put it: “anyone who claims to have visions should go see a doctor.”

Fortunately, our friend Frank-Walter does not suffer from visions, even if he is a visionary in his own way. Please join me in wishing him a happy birthday and many more fruitful years at the forefront of German and international life.

[1] Henry Kissinger (2014), World Order, p. 371

[2] George H. W. Bush, speech to a joint session of the United States Congress, 11 September 1990.

[3] Freedom House (2015), Freedom in the World: Discarding Democracy: A Return to the Iron Fist.

[4] Steven Pinker and Andrew Mack (2014), “The World Is Not Falling Apart”, Slate, 22 December, and Steven Pinker (2011) The Better Angels of our Nature.

[5] Walter Russell Mead (2014), “The Return of Geopolitics” in Foreign Affairs, May-June 2014.

[6] The Economist, “The Sticky Superpower”, 3 October 2015. This is at purchasing power parity. At current exchange rates, the US economy still represents 24%.

[7] Ibid.

[8] http://www.prb.org/Publications/Reports/2009/worldpopulationhighlights2009.aspx

[9] Pew Global Attitudes Survey 2015.