Nuclear security in a changing world

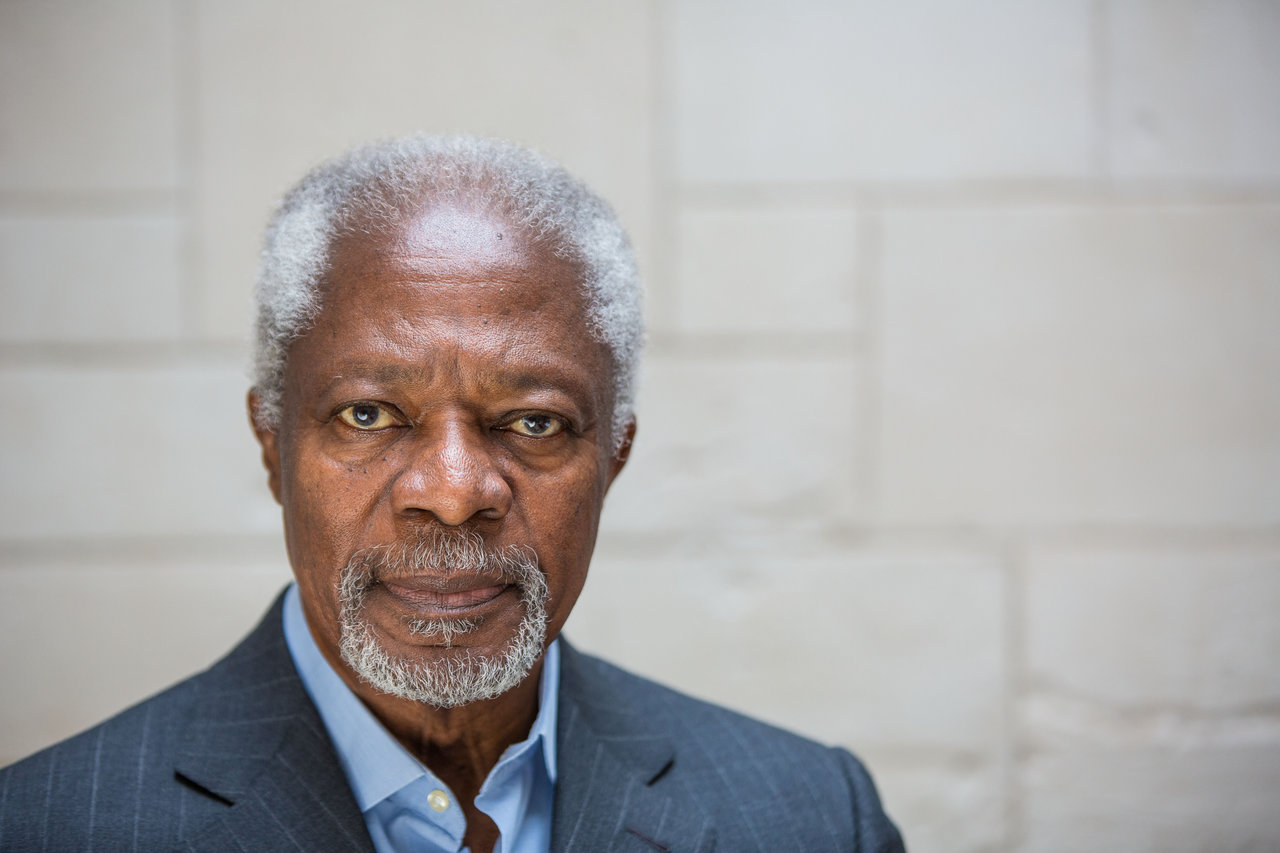

In these troubled times it seems threats to our security come from all corners, but not everyone feels insecure about the same thing. The greatest share of the world’s population is primarily concerned by poverty, disease and climate change. But it is terrorism that makes the most headlines, though it kills comparatively few people. However, one of the most existential threats of all is often overlooked: nuclear weapons. President Obama’s recent visit to Hiroshima is an opportunity to remember their dramatic destructive capacity. In the American president’s own words, “they demonstrated that mankind possessed the means to destroy itself.” The simple yet dramatic fact is why I chose disarmament and non-proliferation as the topic for one of my last major addresses as UN Secretary-General. I argued then that the total lack of any common and coherent strategy to deal with nuclear weapons may well present the greatest danger to life on Earth. Sadly, I see at least three reasons why this is still the case.

First, when military planners look at the world, they are worried. The number of nuclear weapons in the world remains prodigious. Between them the nuclear powers have more than 15,000 nuclear warheads, each far more powerful than those which devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although this may seem few compared with the numbers at the height of the Cold War, new technologies are disrupting the old systems of strategic stability.

Nuclear States are modernizing their arsenals and delivery systems, what some denounce as vertical proliferation. It overshadows the limited progress on nuclear disarmament made in recent years. Even as President Obama called on the nuclear powers to “have the courage to escape the logic of fear, and pursue a world without them” (nuclear weapons) in Hiroshima, his administration embarked on a $1tn upgrade of the US stockpile. After an encouraging period in the aftermath of the Cold War, current geopolitical tensions are once more raising the spectre of nuclear standoff. Longstanding flashpoints, like India-Pakistan or North Korea’s nuclear programme are joined by other shifts in the architecture of global security. China’s rapidly expanding military capacity, combined with its forward territorial claims in East Asia, could push states in the region to seek their own nuclear umbrella. If not managed carefully, the fears surrounding Iran’s nuclear programme could spark a nuclear arms race in the Middle East. In both regions, a certain erosion of confidence in the USA’s security guarantees is also fuelling concerns.

Nuclear weapons are still regarded as the ultimate insurance policy. In an increasingly uncertain world, the temptation to acquire them is great, especially if your enemy has them and you are uncertain about your allies’ commitment. The rise of transnational terrorist groups and the potential of cyberwarfare are creating new fears too. As cyber technology advances, the need to protect existing nuclear facilities from electronic attacks is vital. A simple virus in a nuclear plant has the potential to do terrible damage, with serious consequences for the environment. And terrorism has unfortunately also acquired a nuclear dimension. As violent terrorist groups proliferate, some of which have stated nuclear ambitions, we may have to face the unimaginable. Should a terrorist group succeed in getting its hands on a nuclear weapon, they would unleash devastation that would dwarf the 9/11 attacks.

These threats exist because there are simply too many nuclear weapons and too much nuclear material available in the world today. And much of this is unsecured; a full 83 per cent of nuclear materials remain outside existing standards and protocols, vulnerable to theft and sabotage. This leads me to the third reason why nuclear security remains such a serious issue; the failure of the international community to take necessary action.

Ten years since my address as Secretary-General and more than 45 years after the Non Proliferation Treaty came into force; a common strategy for nuclear security has yet to materialize. The international regime governing nuclear weapons, with NPT at its core, was meant to facilitate the total elimination of nuclear arsenals, a legally-binding contract with the non-nuclear weapon states to negotiate in good faith on nuclear disarmament. But instead we continue to see what I called “mutually assured paralysis”. Disarmament and non-proliferation, which I firmly believe are the twin strands of a successful nuclear security policy, are not being integrated. The last NPT meeting in 2015 ended with acrimonious debate and continued deadlock as the nuclear weapons states refused to even consider concrete steps towards disarmament. Other international instruments such as the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty remain weak without the participation of key nuclear states. There are still no comprehensive, legally-binding international standards for the security of all nuclear materials. As result, many non-nuclear weapon states are questioning whether the existing legal architecture is sufficient to achieve and maintain a nuclear-weapon-free world or even to prevent the further proliferation of nuclear weapons. They wonder whether the NPT “grand bargain” has not become a swindle, when they see the double standards of the nuclear powers. This hypocrisy makes both disarmament and non-proliferation difficult to achieve.

So how do we move forward?

Fortunately, not all is doom and gloom.

Since my 2006 speech, some important steps have been taken, which can and must be built upon. President Obama’s speech in Prague and the series of Nuclear Security Summits have put the issue back on to the agenda and under the public spotlight. These summits have produced important agreements and action on everything from reducing fissile material to updating national safeguards. In just the last six years, 14 countries gave up their weapons-grade material and twelve others, including France, Russia and the United States, have decreased their stockpiles of nuclear materials. International bodies such as the IAEA, multilateral working groups, and the UN continue to do important work. The precedent of states giving up nuclear weapons programmes will hopefully continue thanks to the recent Iran deal. And the international legal and institutional framework does exist, even though it is not being utilized properly.

These facts are encouraging but insufficient to put my mind at rest. The threat posed by nuclear weapons demands better and more lasting solutions. I firmly believe that the only way forward is to make progress on the twin fronts of non-proliferation and disarmament. In calling for action today I draw your attention to that potent symbol during the Cold War, the Doomsday Clock. The minute hand signals how close we are to midnight, the destruction of human civilization. According to the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, it currently stands at three minutes to midnight, the closest to midnight since the darkest days of the Cold War. It will take leadership, dialogue, and negotiation to wind back that terrible hand. Let’s not wait till we face down a major crisis to act; the stakes are simply too high.