State impunity is back in fashion – we need the international court more than ever

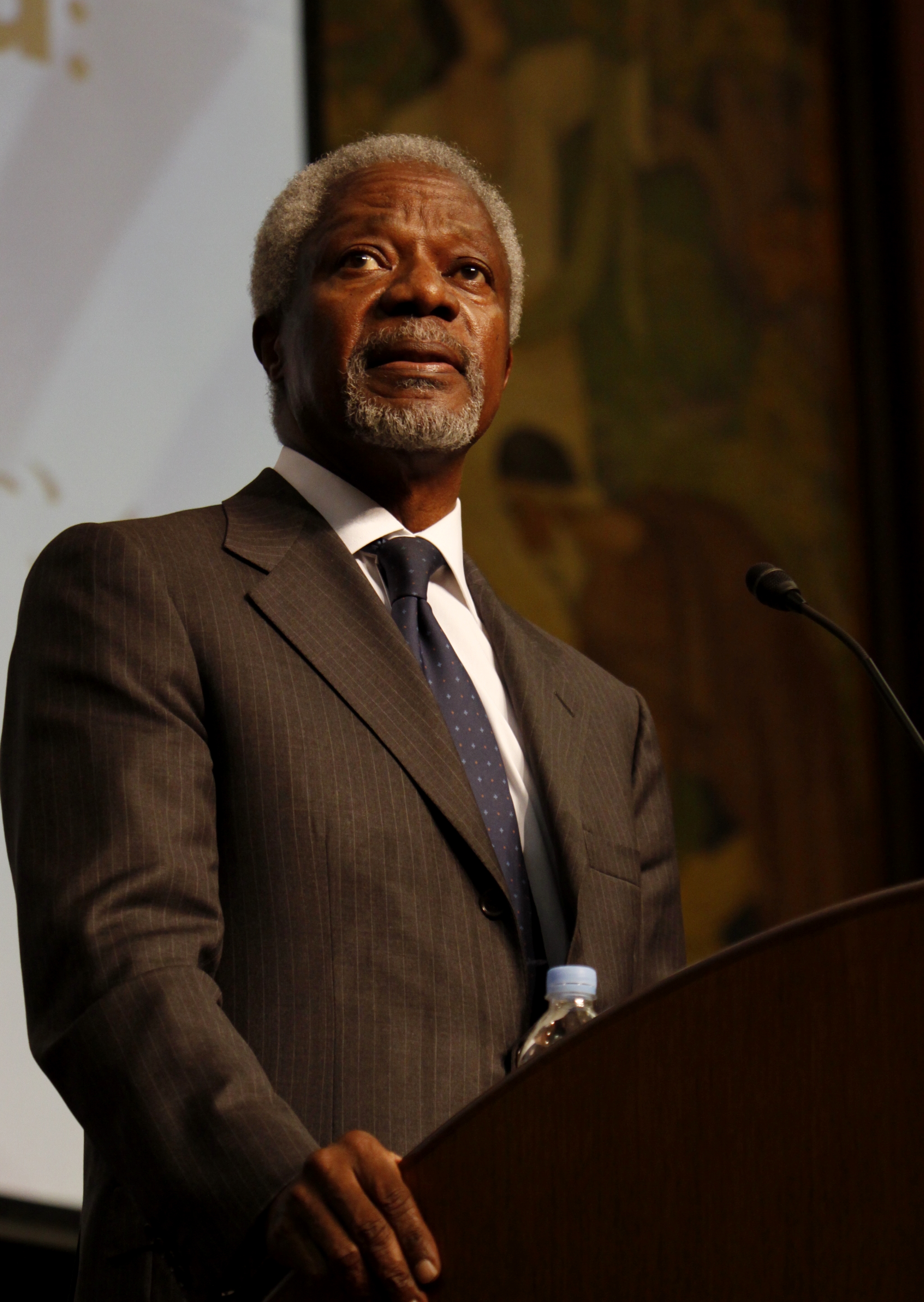

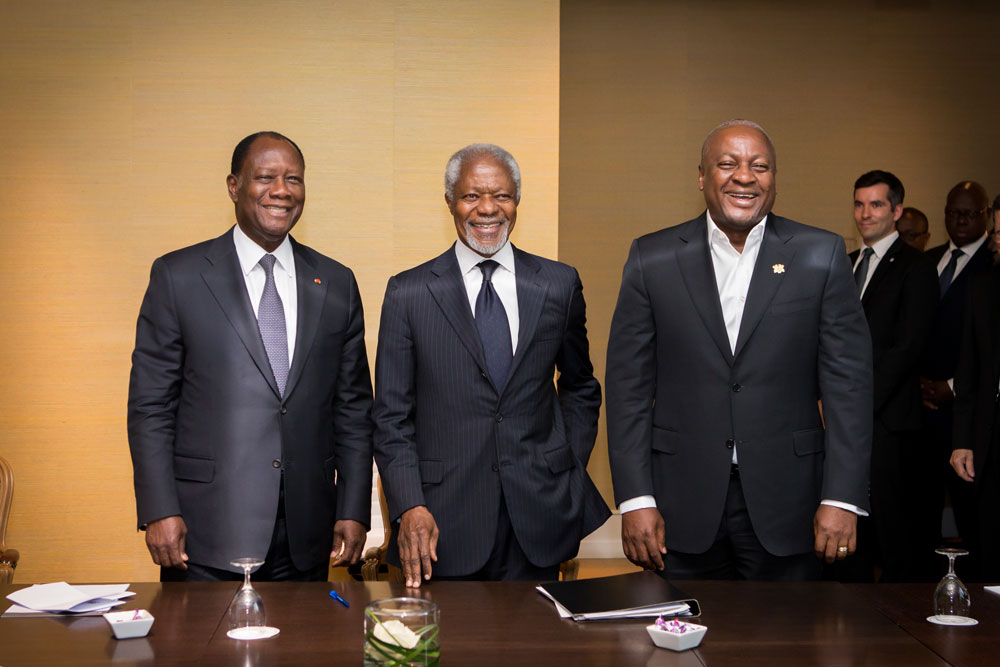

This article by Kofi Annan originally appeared on the website of The Guardian.

The recently announced withdrawal from the international criminal court (ICC) by Burundi, Gambia and South Africa, following earlier threats from some other African countries, has created the impression that Africa is hostile to the court. Let me emphasise, however, that the people of Africa, and particularly the victims of war crimes and crimes against humanity, and members of those communities affected by genocide, stand by the ICC. Most of the continent’s democratic governments stand by the ICC. I stand by the ICC, because the most heinous crimes must not go unpunished.

As the African who opened the conference in Rome in 1998 that led to the creation of the court, I was proud that my continent was its most enthusiastic supporter. Memories of the horrors of the Rwandan genocide were still fresh in our minds. In fact, the first signatory of the treaty was an African country: Senegal. Africa remains the single largest regional bloc, with 34 states party to the Rome statute out of 124.

We also made the most use of the institution from the outset: of the nine investigations on the African continent, eight were requested by African states, six African states referred their own situation to the ICC, and African states voted in support of the UN security council referrals on Darfur and Libya. Kenya was the only case in Africa opened independently by the court, but it enjoyed the enthusiastic support of a majority of Kenyans. They wanted justice for the 1,300 people killed and hundreds of thousands displaced in election-related violence.

The ICC got involved in these African cases because national authorities did not conduct investigations into the massive crimes that had occurred. The ICC does not supplant national jurisdictions, it only intervenes in cases where the country concerned is either unable or unwilling to try its own citizens. Africans deserve justice as much as anyone else, even if their governments cannot always provide it.

Some retort that the African court on justice and human rights should play that role on the continent. Its protocol was adopted two years ago, but it remains largely unratified. For the time being, the ICC remains the continent’s most credible court of last resort for the most serious crimes.

To those who think that Africa is the sole subject of international justice, we should remind them that international criminal tribunals were first set up after the second world war, at Nuremberg and Tokyo. After the cold war, more international or mixed tribunals were set up for crimes in Lebanon, Cambodia and Yugoslavia.

Nor will international justice stop in Africa. The ICC’s chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, an accomplished African lawyer, has opened investigations in Georgia and is conducting preliminary examinations in Afghanistan, Colombia, Ukraine, Iraq and Palestine.

Finally, we need to recognise that the mere existence of the ICC can serve as a deterrent for leaders tempted by violence to shore up their regimes. Be that as it may, we should never forget that justice is its own virtue.

All this is not to say that the ICC is beyond reproach. Most egregiously, the fact that only two of the five permanent members of the United Nations security council – the UK and France – are signatories to the Rome statute (and therefore members of the court), opens the court up to accusations of double standards. It is clearly unacceptable that states with special and historical responsibility for world peace and security should undermine the court’s legitimacy in this way. Those who claim the mantle of global leadership should lead by example. Moreover, the quality of the court’s investigations, its lengthy judicial process and its ability to protect witnesses have been called into question.

These shortcomings must be addressed, but they are reasons to support the ICC’s efforts to rectify them, not to quit the court, one of the most significant achievements of international society since the end of the cold war.

As I have said before, Africa wants this court. Africa needs this court. Africa should continue to support this court. This is why I call on Africa’s democratic governments to take a principled stand this week at the Assembly of States Parties meeting in The Hague to shore up the ICC, a historic milestone on humanity’s journey towards international justice.